Interview: DP Larkin Seiple on Weapons

Aug 28, 2025

Weapons

When cinematographer Larkin Seiple finished the Apple+ feature Wolfs, he was set on taking a well-deserved break. It was going to take a special project to coax him back behind the camera before he’d decompressed, especially for a project outside his home base in L.A.

Then the script for Weapons arrived the day after wrap.

“I read the script in like an hour and I was like, ‘Shit. It’s really good. I don’t know if I’ll ever get the chance to shoot something like this again,’” said Seiple.

Unfolding in overlapping chapters, writer-director Zach Cregger’s follow-up to Barbarian follows a small town’s unraveling after 17 students from a single third-grade classroom disappear overnight.

With the film in theaters, Seiple spoke to Filmmaker about what made Weapons impossible to pass up.

Filmmaker: So, you wrap Wolfs and right away the script for Weapons shows up. What happens next?

Seiple: I met Zach for coffee that week. We really hit it off and were brainstorming right then and there. He had this energy where you could just tell this person knows how to make this movie and is so excited to make this. He offered me the job at that meeting. A couple of months after, we started scouting in Atlanta and another city, then the strike hit and it all [shut down]. We came back a year later and started the process all over again with a different scout. It was trippy, but at least it gave us time to do some prep while we waited.

Filmmaker: How close were you to actually shooting before the strike?

Seiple: A couple months out. It gets a little blurry because the strikes changed different actor schedules, so it kept evolving. We originally planned on trying to shoot it in the winter because we wanted it to be dreary and overcast. We wanted this malicious presence over this town. When you watch the movie now, it’s the opposite of that with these very bright, sunny day exteriors. At first I was like, “We’ll do something in the grade. We’ll find a way to knock it back.” We tried that, and it just felt wrong, like we were hiding something, so we were like, “Let’s embrace the sun.”

Filmmaker: I believe this is the first horror film you’ve shot. Are you a fan of the genre?

Seiple: I have read a lot of horror scripts, and they’re really fun to read because they are often mysteries slowly dealing out information and you have to try to figure it out before you get to the end of it. I’m a fan of that, but I don’t watch that many horror movies. I told Zach when we met, “I don’t do horror movies. That is not my background.” And he was like, “Is that a problem?” “No, I think I can make this look great. I’m excited for this.” “Good, because I’m not looking for a horror movie DP. I’m looking for a DP that can make something [unique] with me.”

Filmmaker: Magnolia and Prisoners are the two main references I’ve heard Zach talk about. Were there any horror films he wanted you to watch?

Seiple: We watched Magnolia, but more for the zeal of that opening sequence and how Paul Thomas Anderson was able to show all this information and have fun doing it. That was the main reference from Magnolia and influenced how we shotlisted that whole opening. Zach had storyboarded the sequence already, but once we got to set and started seeing the locations, we started rethinking how to do it. Prisoners was a reference as well, but more so when we were thinking about shooting in winter and wanting it to feel moody and overcast with a sense of dread. We also looked at some jump scares. We watched 28 Weeks Later. In that opening sequence where the zombies attack the farmhouse, I watched it on a laptop in a bright room and had forgotten what the jump scare was, which is when the camera pans literally into the eye of a zombie who’s been next to this character the whole time. I yelped. [laughs] Jump scares are about subverting your expectations. You’re looking here, but really the jump scare is over here. Zach is a horror guy, so that came very naturally to him.

As I’ve progressed [in my career], I try to do less references and go more from the shotlisting process. You get to be pretentious and have these big ideas while you’re figuring out what the rhythm of the scene is and what you can do to make it singular. For this one specifically, there’s so much that happens and it was all about, “How do we show all this in one shot without trying to be fancy? How do we propel it forward without making it cluttered in the edit?” We want the audience to be able to seamlessly pick up all this information and understand why this character is making this decision without doing it in five shots, because we also didn’t have time to do five shots with our schedule.

Filmmaker: How long was the shoot?

Seiple: We started at 47 days. Once we realized how complicated the action sequences were, we ended up closer to 50.

Filmmaker: One way Weapons did remind me of Prisoners is in the lighting. Though the camera movement is sometimes stylized, the lighting leans into realism.

Seiple: We wanted it to feel visceral and real, then we would enhance certain moments. The lighting was never meant to feel flashy or stylized. If there’s a bit more contrast [than what might be considered “realistic”], that’s just to give it a malicious nature, to make it feel like something is coming. That plays along with the score. There’s this war drum element that’s happening throughout. These characters are marching towards their fate. A lot of it wasn’t a big conversation about how it should be lit. It was like, “We’re in the police station, so it should be fluorescence because that’s what would be in there.” For day exteriors we did very little lighting. A lot of it was timing the schedule around backlight, because we were shooting at the time of year when the sun is really gross in Atlanta. For the chase sequence between James [Austin Abrams] and Paul [Alden Ehrenreich] or the gas station sequence, we would shoot one direction from morning until noon and get all that coverage, then turn around in the afternoon once the sun moved and shoot all of the other side.

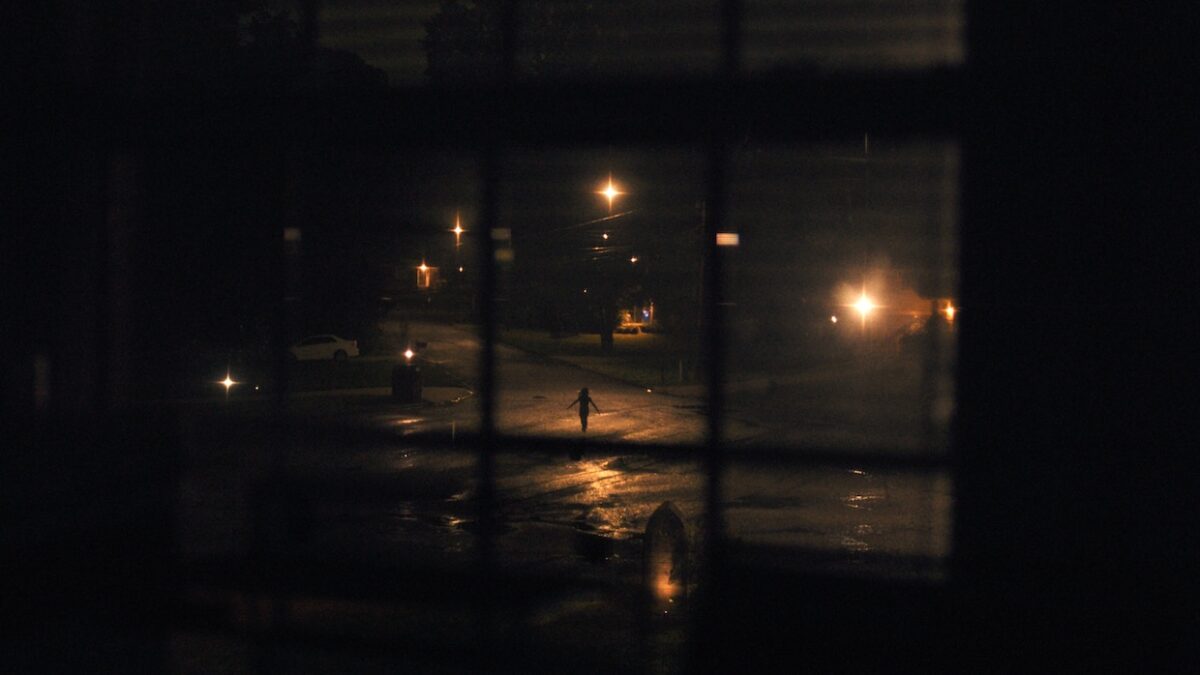

For the night exteriors of the kids [leaving their houses], we wanted to not have it be moonlit but still be able to see the shapes. It was less about seeing the kids and more about feeling them. We also wanted that to feel less perfect as opposed to, like, six condors and a balloon light. We definitely had to use a condor because the streets were so dark. We shot max ISO in camera and were just kind of “thoughts and prayers” for some of the wide shots, because we couldn’t light a wide shot of three city blocks. It was a challenge, but I think that aesthetic is what makes it compelling because hopefully you believe a little bit more than if it was more dramatic or dreamy.

Filmmaker: I don’t know how many of the 17 kids we actually see sprinting into the night in that opening sequence, but it’s a lot of them. Was it difficult to come up with that many different yet interesting wide shots?

Seiple: It was a lot of us doing our normal 12-hour prep day, then me and Zach getting in the car and being like, “Well, our [hero] house is here and there’s six neighborhoods around it. Let’s go find some shots.” We found probably 30 different houses to shoot. We’d drive around and say, “Oh, if you look through the backyard of this house, you can see this other house and there’s a porch light there.” There’s this amazing drain in the movie, this sewer underneath the grassy hill that you see in the opening. That was something we found while scouting. We used the top of that sewer for one of our night shots where the kids were running across in silhouette against a house. So, a lot of it was just doing that extra work to find each location, then we had to cull them down. We actually made an animatic of all of our stills from those scouts and put it to the George Harrison song [“Beware of Darkness”] so we could figure out how many shots we needed for the sequence. It was an arduous process. We would shoot a normal day, then I would go and join a second unit after we wrapped and shoot for a few more hours to get the [montage of the] kids. We had about a week to shoot those, and we were shooting in summer, so we could only shoot from 9 pm, when it got dark, until midnight [when the kids had to be wrapped]. So, we had three hours and then the kids became pumpkins, as we say.

Filmmaker: Circling back to lighting, the one location where you get to lean into the horror a bit more is Alex’s house, which is very ominous with newspaper on the windows keeping the sunlight out.

Seiple: That was all on set. We built big soft boxes around the house to be able to control the glow and, depending which way we looked, would lower the intensity in the windows in shot and bring up the intensity for the windows [not in frame]. When we designed it with [production designer] Tom Hammock, we made a big push to do a lot of windows. Even in the middle of the building process, we would walk through once the walls were up and be like, “Actually, can we make another window here?” The trick to it was that if we had enough windows Alex would always be silhouetted, so it became less stressful trying to light him in the space. As long as we could see his path where he was going, we could let the scenes evolve naturally. Also, because there’s so many complicated camera moves and oners that start in one room and go to another, there wasn’t a lot of space to add lights.

Filmmaker: What did you end up shooting with?

Seiple: The Alexa 35. It was fun because we actually got to test it against film. In prep I brought an Alexa 35 and an Arri LT out to the Alex’s house and did portraiture work with all of the different actors in similar lighting setups—day exteriors, shots through windows, shots in the house, underexposed shots. Then I got to take Zach to a theater and project all of it, and we got to talk about what we liked and didn’t like about film and digital and the benefits of both. We ended up landing on the Alexa 35 because we could get the skin to a really interesting place and were able to try to mimic the way that film rendered skin the best.

Filmmaker: Were those tests more just a point of comparison or was film ever a realistic possibility?

Seiple: Probably not, especially given the amount of night exteriors we had and also working with child actors where you need to roll. It was never really in the cards. It was more for research to be able to talk about what we love about film and how we could bring that over to digital. Digital is getting really good. When we were comparing the tests, it wasn’t necessarily night and day. The place where I notice it is that film resolves color in a way that when there’s a gradient of color, like going from an exposed piece of skin to a shadow, it’s really beautiful and natural. In digital the image tends to break up or fall apart in those situations. You notice it in wide shots. It’s just how it renders color in the trickier places of the curve, basically. But it was good to see that because then we were able to work with our colorist Alex [Bickel] to try to build a LUT that literally added flesh back into the shadows, adding a bit of red and orange and texture back into places that would go dead or dull.

Filmmaker: When we talked for Wolfs, you said you shot a lot of that movie with the Alexa 35’s Enhanced Sensitivity Mode. I think it goes up to like 6400. Where did you tend to live when you used that mode?

Seiple: We would go to 2560 and for some exteriors would go past that by like half a stop. The LUT that we used also had a half stop built in. So, the LUT would force me to overexpose by a half stop as a safety mechanism. Since then, we’ve built one that I wish I had used on Weapons that forces you to overexpose by two stops so you can shoot something really dark and moody and know it’s all there. We did a low light test on some of the streets and shot night exteriors with just the practical streetlights just to understand what was there, and there was very little. For some reason, all the streets we chose were like the darkest streets in Atlanta. [laughs] So, we always had to bring in something. A lot of it was just adding practicals to doorways or lamp posts or little, tiny dots of light on guardrails. If we got lucky, we were able to bring in a condor and just add an edge to the whole thing.

Filmmaker: How about lenses?

Seiple: We did a really fun lens test. I took Zach to Keslow in Atlanta, and we brought out a ton of lenses just because I was like, “Let’s talk about everything.” We had originally discussed shooting it spherical, so I showed him Master Primes, Super Speeds and some more vintage glass. Then I showed him some dramatic anamorphics and he was like, “Definitely not that.” As we got to, like, the eighth set of lenses, he was like, “These are great, but I can’t really notice the difference. You can maybe try to point it out to me, but when you show me these three lenses back-to-back it just feels the same.” So, I said, “Let’s try these lenses out” and threw on a Master Anamorphic and he was like, “That! That just feels like a movie. I can’t express what it is about that lens, but when I look at this shot in a boring house it now looks cinematic.” So, I was like, “Well, I guess we’re shooting anamorphic.” “Those are anamorphic? They’re not bending and distorting.” “Yeah, these are the fancy Arri-style ones that kind of look like Master Primes.” So, we brought them to stage and tested them. We then took them and did all the hair and makeup tests with the actors to make sure it was still the right choice and we loved it. I also showed him the Canon K35s, which wide open feel a little unhinged. They’re sharp, but they get a little glowiness to their highlights. We used those for Austin Abrams’ chapter as James. They just felt like his character. At one point we talked about doing different lenses for each chapter, but it started feeling tedious and unnecessary. It felt better to unify almost every chapter under the same aesthetic because they’re all kind of in the same trouble. But James’s chapter is so different from everything else that it felt right for his. We used wider lenses for him. We were closer. We just wanted to feel his character more because the shot structure is very different in his chapter compared to the others.

Filmmaker: You had just come from working with Austin on Wolfs. Had Zach already cast him when you came on board?

Seiple: Yeah. I was picking Zach’s brain and asking him who was in the cast, and he was like, “You’ve got to meet this guy Austin Abrams.” I was like, “Oh, I know Austin very well. He’s going to be amazing in this.” And Zach was like, “Yeah, he’s going to lose 30 pounds to play this role.” And I was like, “He doesn’t have 30 pounds to lose.” [laughs] When we did the hair and makeup test, Austin had the gnarliest beard you’ve ever seen. I loved it. We ended up shaving it and it broke my heart. Zach was like, “If we don’t shave that beard, people are not going to like him, and you need to like this guy. He makes terrible choices and is probably not a good person, but you need to believe he could be a good person, and that beard is holding you back from that.”

Filmmaker: There are some funny parts in the movie, but the only bit that made me laugh out loud was when Austin’s character is robbing a house and he’s grabbing their DVD’s and he’s like, “Oh fuck, Willow!” Was that in the script or an ad-lib?

Seiple: No, that’s just Austin being Austin. We were really blessed. All the actors enjoyed their roles and liked to improvise or add something to it. Also, because we’re shooting all this out of sequence, we’d spend a week doing Austin or a week doing Josh [Brolin]. I felt like the actors got kind of amped when it was [their turn to shoot their chapter]. It was like, “This week are my scenes!” There was a real energy to it. A lot of the days we’d be like, “Guys, we have to move on.” The actors were having so much fun, but we’d have other shots to get.

Filmmaker: When you’re shooting a scene that’s going to be experienced twice from different characters’ perspectives, like Austin’s confrontation with Alden Ehrenreich’s cop, obviously you’re shooting both sides of that on the same day. Zach talked in an interview about how the approach would be different depending on whose POV you were in. So, for Austin’s side, you’re shooting Alden from lower angles and making him more menacing because that’s how he feels to Austin’s character.

Seiple: We did play with that. The first time we shot Alden talking to Austin, it’s a neutral two-shot. They’re on the same level in a way and Alden literally says, “I did you wrong. You did me wrong.” Then when you get to Austin’s [chapter], to him he’s been assaulted by this cruel, evil cop. We talked about every character’s chapter having a theme when we first sat down. For Alden’s chapter, the world passes him by. He’s like a buoy. All these things happen and he’s just adrift and decides to make the wrong choices. There’s a lot of profile shots of him because he’s never necessarily the hero. All these things are moving around him. Whereas Justine [Julia Garner, as the missing kids’ teacher] is very much being preyed upon, so the camera’s more paranoid. It’s wrapping around her. It’s over her shoulder. We’re constantly moving with her. Archer [Josh Brolin, playing a missing kid’s father] is very much a hunter. He’s on a mission. So, there’s a lot more shots from behind him or in front of him pulling and pushing and he is dead center. It’s fun to have these ideas at the beginning. We had a big talk about them, and we got excited and then when you start shotlisting, you completely forget you ever had that conversation. [laughs] It’s great to have big, pretentious ideas, but it’s also nice to just shotlist based on what the scene needs and what makes sense. Then you find those ideas [organically] working their way in again.

Filmmaker: My favorite two-shot combination is when Austin first visits Alex’s house. As he’s trying to get out the front door, you’ve got the camera rigged to the door on the inside. Then once he escapes, you do this long zoom from across the street on the front door as he runs out and the door slams shut behind him. I love that zoom.

Seiple: That was really fun. For the door mount we wanted to enhance Austin’s fear and inability to get out with the daylight peeking in. For the zoom shot, we wanted it to be almost poorly done. We didn’t want it to be smooth. We wanted it to have this nervous energy. It’s actually a zoom dolly. We built 30 or 40 feet of track across the road. It was a really hard shot for the operator on purpose. [Camera operator] Mike Fuchs is trying as hard as he can to make the zoom normal, but we literally tried to make it so that the camera had to shake when it zoomed in.

We had about nine shots to do that day of James finding the Lilly house and then breaking in. We used rain towers, but we had to wait until dusk because we couldn’t have rain and sun. So, in order to pull off all nine shots in an hour and half, we spent two or three hours rehearsing all of the shots, setting up the track and figuring out the camera moves and blocking. Once we were confident in the creative and technical choices we waited until dusk, which just felt like a cloudy day, then knocked out all of the shots at a breakneck pace. We ran out of light at the end, and you’ll notice that Austin has a kicker from a street light on him when he first finds the house because it was so dark the city lights turned on and we had no way to flag them off.

Filmmaker: Did you do the zoom on something older and funky to get that imperfection you were after?

Seiple: We used the Angenieux Optimo 24-to-290mm. That is the workhorse of your big zooms. We played with older zooms originally, but they get really funky and I didn’t want to take the audience out of it by having glass where the contrast felt really different and you start having crazy chromatic aberration on the edges. Just the end of a long zoom itself will always feel a little gnarly.

****Spoilers****

Filmmaker: Let’s finish by breaking down a few specific shots. We talked earlier about jump scares, so let’s get into the ones during Julia Garner’s dream sequence. I don’t remember exactly how far into the film this comes, but it was long enough that I started to think, “Maybe this isn’t going to be a jump scare kind of horror movie.” Then you hit me with two of them back-to-back in that dream.

Seiple: One of them is the classic jump scare thing where she wakes up from a nightmare and your brain is like, “Is she still in the nightmare?” She looks around her house and peers out around her door and nothing is there, and I think everyone should know at that point when the main character takes a deep breath that a jump scare is coming. So, she leans back [and there’s a blur cut as the camera tilts up to see Amy Madigan’s Aunt Gladys on the ceiling]. We shot half of it on our real set and tilted the camera up to an empty ceiling, then rebuilt the ceiling upside-down on stage and cut a hole out of it so Amy could lean a certain way. When you have someone on the ceiling, you’re like, “How do we make this look scary?” If she’s standing straight up, you can’t really see her. So, she had to lean backwards, and we had to bring in a support for her back. It became this cumbersome thing to try to make this image that will hopefully haunt you.

There is another jump scare in Josh’s dream when he’s talking to his son in his bed and there’s a splash of Amy. We shot that a couple of times using the same lighting. It was really creepy, but it wasn’t scary. So, I was like, “I need to change the lighting.” As I’m thinking about that, makeup goes in to touch up Amy and a grip had this gross flashlight that he pointed at her face for the makeup team [to be able to see]. I’m looking at the monitor and I’m like, “Oh my God, Amy looks like a ghoul.” So, I asked Zack to give me one more take and when he yelled action I took the grip’s flashlight and swung the light on Amy’s face, and it brought out all of these textures. You can see Amy’s lipstick on the weird little baby teeth that we gave her.

Filmmaker: Jump scares are often so dependent on a sound sting to really sell them. On set, can you actually tell if one is working?

Seiple: The sound is huge. There’s another sequence towards the end of the movie where Josh is looking through a basement with a flashlight and runs into [Gladys] in the corner. We actually re-shot that. Just getting the kids to stand still and pretend they’re numb was a challenge. The kids would smile or crack or itch their face in the middle of a shot. So, we had a hard time getting it and did three or four takes of Amy jumping out of the dark [at Josh] and it was like, “Should she be standing? Is she crouching?” We ended up going back the next day and reshooting it with her in a different position and that’s the one that made it into the movie. When we were in the color grade and had the sound on, the score would make me jump at that every time even though I knew it was coming. When you see the movie in the theater with the score, all of a sudden the imagery is much more potent.

Filmmaker: Another shot sequence I loved was toward the finale where Alex’s parents are guarding Madigan’s door, with this line of salt as a threshold. There’s a great shot of the parents where they’re uplit by a nightlight, then an insert of Alex’s foot stretching over the salt.

Seiple: That hallway is used in the movie a lot and I was really nervous about that scene. I was like, “We can try to do this like the nightmare sequences where there’s just ambience, but there’s no real place to hide the light or bounce it into the ceiling. We see the whole thing.” So, early on, I was like, “Can we please have a nightlight in the hallway?” There were other ways to do it where we’d pull the ceiling and have a soft top light throughout the hall and then post would have to add the ceiling back, but that always felt weird. We had to do some other tricks for that scene. There’s a shot following Alex’s feet down the hall that we did on a probe and the probe only goes to, like, an F8. So, that shot was wildly underexposed, but in the grade we were able de-noise it, clean it up and make it work. The salt line shot was something we had actually forgotten to get because our schedule was so crazy. That was one of the very last things we shot. We had to move to the basement set and do it on a random wall with a probe. To get a really deep stop we had to pull the nightlight in the wall and just bounced what’s called a zinger, a very hot light, just out of frame so you get this gradient on the salt and all this texture on the shoe.

Filmmaker: Did you use the same Laowa probe lens from Everything Everywhere All at Once?

Seiple: Yeah, but the newer version. The one on Everything Everywhere I think goes to an F11 and had a built-in LED ring, which was great. The new ones come with a three-lens set. As opposed to just a straight shot, they have one that’s at a 45-degree angle and I believe one that’s at 90 degrees. So, we were able to offset it and put it down. We also used the probe for [the shot of Benedict Wong’s school principal] climbing under the car at the gas station. Cars are generally too low for anybody to crawl under. We had a huge debate about how to do this and ended up lifting the car on jacks and adding the tires back in post in order to get all the actors under the car. Our VFX team did a wonderful job. It’s a pretty frenetic sequence, but maybe if you look at the tires you can tell.

Filmmaker: In that moment, you’re going to be looking at the bulging-eyed principal, not the tires.

Seiple: Right. Why would you look at the tires when you have a monster crawling under a car chasing someone? We used the probe there to get underneath the car and pull back and spin him around when Josh comes over to kick him. There were all sorts of camera movement challenges on this, from the Steadicam oners in the liquor store or the end sequence where we’re chasing the little girl through the house, which is all handheld.

Filmmaker: Right, she goes through a living room window and the camera follows her.

Seiple: We had some of the window there—just the structure of it, none of the glass. She would burst through and then our camera operator and boom operator would both follow after her. My buddy Connor O’Brien operated on that. He came out for the gas station sequence too. Sometimes the biggest challenges are shots no one thinks about, like tracking Julia and Benny in these really narrow aisles with hard 90-degree turns going full speed. Connor came out because he is a professional inline skater. He had a Ronin and would ramp up, then chase Julia on skates and have to hard stop at the end in order to get the speed we needed to make it feel like they were actually running.

Filmmaker: Was he on the Ronin too when he went through the window?

Seiple: He was handheld for that. He was just sprinting behind one of our stunties. We built a backpack for [the camera] and stripped the Alexa down to just handles. Connor is a pretty strong dude, so he was able to hold it front-mounted, which can be tricky for some people. Bizarrely, our biggest challenge was actually getting video signal. We had our camera team hiding transmitters throughout the house so that our AC could pull focus.

Filmmaker: There’s a wide shot that’s in the trailer where this horde of kids comes smashing out the front of a house. You convincingly create the illusion that it’s actual kids.

Seiple: It was usually a combo. We had stunt actors that were about the same proportion as the kids. They would lead the charge through anything breakable, then the kids would follow or go through the doorway. We actually did a lot of the shots on greenscreen with the stunties just so that VFX could have a reference for how the windows break, what happens with the structure of the walls and things like that. There’s a shot where Gladys runs through a house and the kids run through behind her and we did that on a repeatable head. So, we’d shoot the shot with Gladys, then go back and do it again with a stuntie, because they were actually breaking glass and falling over things, then do it one more time with the kids, with all the debris swept away and the glass removed. Then we blended the plates together, so it feels just like chaos.

Publisher: Source link

Erotic Horror Is Long On Innuendo, Short On Climax As It Fails To Deliver On A Promising Premise

Picture this: you splurge on a stunning estate on AirBnB for a romantic weekend with your long-time partner, only for another couple to show up having done the same, on a different app. With the hosts not responding to messages…

Oct 8, 2025

Desire, Duty, and Deception Collide

Carmen Emmi’s Plainclothes is an evocative, bruising romantic thriller that takes place in the shadowy underbelly of 1990s New York, where personal identity collides with institutional control. More than just a story about police work, the film is a taut…

Oct 8, 2025

Real-Life Couple Justin Long and Kate Bosworth Have Tons of Fun in a Creature Feature That Plays It Too Safe

In 2022, Justin Long and Kate Bosworth teamed up for the horror comedy House of Darkness. A year later, the actors got married and are now parents, so it's fun to see them working together again for another outing in…

Oct 6, 2025

Raoul Peck’s Everything Bagel Documentary Puts Too Much In the Author’s Mouth [TIFF]

Everyone has their own George Orwell and tends to think everyone else gets him wrong. As such, making a sprawling quasi-biographical documentary like “Orwell: 2+2=5” is a brave effort bound to exasperate people across the political spectrum. Even so, Raoul…

Oct 6, 2025