“The Nova Convention… a Free Artistic Experiment”: Aaron Brookner and Rodrigo Areias on Nova â78

Aug 24, 2025

Nova ’78

Aaron Brookner and Rodrigo Areias’s Nova ’78 centers around the Nova Convention, a late ’70s avant-garde extravaganza that took place at NYC’s now defunct Entermedia Theater (Second Avenue and 12th Street) in honor of William S. Burroughs’s return to the U.S. after living more than 20 years abroad. It was also a great excuse to gather a who’s who roster of counterculture icons to perform in the presence of the postmodern wordsmith who’d profoundly impacted them all. That would include Patti Smith and Lenny Kaye, Laurie Anderson and Julia Heyward, Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky, Brion Gysin, Timothy Leary, Merce Cunningham, Philip Glass, John Cage, Jackie Curtis, Robert Anton Wilson, Terry Southern, Frank Zappa and the list goes on. Quite the happening indeed! (Even without Keith Richards, who had to cancel at the last minute and was replaced with Zappa. Needless to say, no ticket-holders in the jam-packed audience took Smith up on her offer of a refund.)

And just as remarkable is the fact that footage of the three-day event — shot on 16mm by Howard Brookner, Tom DiCillo and Jim Lebovitz with Brookner and Jim Jarmusch on sound — was only recently discovered in 2022 by an archivist at the John Giorno Foundation. Who then naturally placed a call to Aaron Brookner (Uncle Howard), who’s long been on a restoration endeavor, from 1983’s Burroughs: The Movie to 1986’s Robert Wilson and the Civil Wars (screening at the upcoming NYFF), to keep his late uncle’s all-too-brief body of work forever in the public eye.

Soon after the film’s Locarno debut Filmmaker reached out to the Europe-based co-directors to learn all about Nova ’78 and the challenges of bringing a lost film to the big screen.

Filmmaker: So how did you two meet and ultimately decide to collaborate on this project? And how exactly does co-directing a lost film work?

Brookner: I first met Rodrigo when he brought the project Listen to me and [producer] Paula Vaccaro to co-write. Since it was set in London we ended up producing it together. The project had many challenges: children on set, a first-time filmmaker, limited budget and schedule, and then the pandemic. But the film did very well, winning two Lions in Venice and dozens of awards, including Best Script. Along the way Rodrigo showed unwavering energy and positivity, and we became close. I admired his spirit.

Few people realize the immense work of rescuing and restoring an archive, or the challenge of keeping it relevant. Between 2012 and 2015 I uncovered most of my uncle’s archive, including partial material from the Nova Convention. Digitizing, syncing and grading took Paula and I a decade, with only small grants, investor debt and our own company resources.

By January 2022 we finished the last roll, exhausted. A month later John Giorno’s estate called: they had found 44 more negative rolls in his Long Island storage. That meant 440 minutes, and I felt it was likely the missing Nova material. Rodrigo heard my desperation and, in his rock and roll spirit, quickly proposed helping with scanning and restoration with support from the Portuguese Film Institute. Once we did that work in London we finally saw the Nova Convention as a whole, and its relevance was undeniable.

The Nova Convention was an exchange of ideas, a free artistic experiment, urgent then and now. My uncle began filming it with William Burroughs, but their friendship led to Burroughs: The Movie, leaving the Nova film behind. Knowing the footage intimately, I was comfortable editing and writing; but I wanted another perspective, partly because Nova was collaborative in spirit. Growing up in northern Portugal, Rodrigo had been influenced by these artists, while I approached it as a New Yorker in London. That synergy felt right.

We worked in spells, balancing it with other projects and scarce resources over the years. Rodrigo began his artistic career as a musician, and I often felt like we were making a record, which suited this sort of concert film. It was not always easy but in the end we each brought our best, and it served the project well.

Areias: Yes, we met during the production of Listen, a film that Aaron co-wrote and co-produced, and for which I was the main producer. From that moment on we tried to develop several other projects to do together. This one came naturally. I already knew Burroughs: The Movie by Howard Brookner and Uncle Howard by Aaron when I was invited to embark on this adventure.

The co-direction was a natural process between two perspectives that easily complemented each other. Mine was the perspective of a fan of all the people who took part in the convention; and my main concern was to respect the authors of the images in order to make a film that, in the late ’70s or early ’80s, could never have been made in the way it can be done today.

Filmmaker: Could you talk a bit about the editing process? How much footage were you actually dealing with, and how long did it take? Were many “darlings” left on the cutting room floor?

Brookner: More than “darlings,” entire approaches were left out. We used only footage from 1978, even though the archive runs until 1983. My uncle filmed an astonishing amount with Burroughs, all on film, and every new collaborator is floored by how much there is. What we used is only the tip of the iceberg.

I once drew a diagram with Burroughs and the Nova Convention as a stone in water, sending concentric circles outward, the epicenter of a movement in a particular time and place. Turning that into a film required not only editing but also writing. It became one of the most challenging projects I have worked on, as there are no interviews or explicit narrative to explain anything.

To me a key part of the writing was creating a counterpoint to the Convention, which came from the trip to Colorado. This was the very first thing my uncle shot, about a month before the event, with Jim Jarmusch and Burroughs in Boulder, Eldora and a ghost town. There were mountains, open air, guns, smoking, drinking and free conversation. The intimacy between them deepened, and Burroughs emerged as profoundly American, and I felt the same about Howard and Jim. Linking Colorado with the Convention gave the film its narrative line.

The film is about discovery, shaped just enough so the viewer does not get lost, yet open enough to allow ideas and people to be discovered. We approached the film in various ways, as research, and we were crafting the edit almost until the Locarno premiere!

Areias: The amount of archival material was absolutely amazing. There were more than 40 hours of footage and over 60 hours of audio. We started working together in 2022, so it took approximately three years to get to where we both wanted it to be. The editing was done with Tomás Baltazar, a close friend and longtime collaborator (and the editor of Listen), who is also an enthusiast of the whole cultural reality we are portraying.

As for “darlings” left behind, there were many, mostly related to a different kind of film we could have made. There was a lot of great material about Burroughs’s personal life that we loved, and even edited, but eventually left out.

Yet when the idea of a Nova Convention–focused film prevailed it was easier to concentrate on the performances, while keeping the clapboards and Howard Brookner’s appearances, so the sense of an old unmade film would always remain underneath.

Filmmaker: What were some of the biggest revelations you discovered while digging through the archive? Anything that made you reassess Burroughs or Howard?

Brookner: So many. What struck me most were the ones that speak to today. The idea of resisting fundamentalism on all sides felt urgent, as did the recognition that attacking one minority is never just about that group but about all minorities. Burroughs opposed Proposition 6, which sought to ban homosexuals, and even anyone who supported them, from teaching. He pointed out that its backers were also hostile to Black people, Jews and other minorities.

I was also fascinated by the debates between Burroughs, Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky over Iran and the fall of the Shah in 1978, and the role of the U.S. At a time when discourse now feels so polarized it was striking to see people of different ages, backgrounds and politics engage with mutual respect, shared influences and a spirit of experimentation. There was none of the “if you don’t think like me you’re the problem” dynamic.

After almost 15 years with Burroughs and Howard, my greatest revelation is an even deeper respect for them. They were ahead of their time: a perfect pairing of a subject who could see and articulate the world with piercing clarity, and a filmmaker who could capture it with the language of cinema.

Areias: Aaron had been working with this archive for a long time, while for me almost everything was new. So I had a completely different approach, which I think brought something extra to the film. Because of my distance from Howard, I focused much more on making a punk film with the Nova Convention material that struck me from the beginning — a film that would have been extremely difficult to make at the time it was shot. We didn’t care about shots out of focus, zoom-ins, or any other kind of “technical problems” that broadcasters used to criticize in traditional documentaries.

Filmmaker: Pretty much every scene features a legendary counterculture writer, musician or figure. (And also a dancer, as Merce Cunningham makes a fittingly bizarre appearance.) Yet you only specifically identify each of these characters at the very end, which made for a fun guessing game for me. But did you ever worry you might alienate audiences with your decision to do away with any explanatory elements and leave much of the context offscreen?

Brookner: I worried about that, since I wanted the Nova Convention to be accessible. But labelling people never worked, it broke the free-flowing nature of the material. Adding explanations beyond the opening text also felt false. The Convention was unique and surprising, and any attempt to categorize it seemed trite.

The point was discovery: to let viewers encounter something new at every turn without expectation or judgement, as if they were there alongside Burroughs, around whom the whole movement orbits. Sometimes a performer is named, sometimes not, and in the end we saved the credits for a playful sequence set to an original track by The Legendary Tigerman.

Areias: We discussed this until the very end. We were aware that we might alienate audiences with this decision, yet it felt like the only possible way: to remain faithful to what happened in that moment, forcing the audience to dive into the event itself.

We also included the presentations of who was performing whenever possible, so we often hear who is going onstage during the film. But we knew that saving the full info until the end in a farewell party-style conclusion would help the audience relate to the performances as flashbacks, adding another emotional layer at the film’s closing.

Filmmaker: Aaron, you’ve pretty much made your late uncle the focus of your career and life, even leading the Howard Brookner Legacy Project, so I’m curious to hear how your relationship to him has changed over time. Has keeping Howard’s oeuvre alive become an obsession? A burden? A labor of love? (Some combination?)

Brookner: My first film was a short documentary on Black cowboys in Brooklyn, which won an award at its first festival in 2004. At that moment I emphatically declared that I was embarking on a career in independent filmmaking. Since then I have written films and series, produced features for first-time directors, directed a film in Taiwan and developed many other projects. I also became a partner in Pinball London, and together with Paula we have built a company that has earned over 100 awards worldwide and endured for 16 years, which is no small feat.

When I opened the cans of my uncle’s work (pun intended!), I had no idea what it would entail. I somehow felt I became responsible for the stories inside. Without those efforts Burroughs: The Movie would have been forgotten, as would the story of Howard and that pre-AIDS era. Restoring his second film on Bob Wilson, the CIVIL warS, was another major challenge; but after a decade of work Bob and I finally watched it together last June at Cinema Ritrovato shortly before his passing. Many were shocked because most people did not even know the film existed, and yet it portrayed what was arguably the greatest risk Wilson ever attempted as an artist. The same is true of the Nova Convention: it would have disappeared without years of work to find and shape it.

Each restoration connects the past to the present, carrying stories, artists and ideas forward. I do not see it as a burden or even a mission, but as a responsibility to preserve what I uncovered through filmmaking. I have invested time, effort and resources, but I have also gained enormously as a director, writer, producer and thinker. These histories have shaped me and continue to shape the new films I am writing and directing which, fittingly, all explore family and characters navigating treacherous new terrains. Finding a definitive home for my uncle’s archive now feels like the final frontier and the greatest remaining challenge. I only hope it will not take me another decade to achieve.

Publisher: Source link

Erotic Horror Is Long On Innuendo, Short On Climax As It Fails To Deliver On A Promising Premise

Picture this: you splurge on a stunning estate on AirBnB for a romantic weekend with your long-time partner, only for another couple to show up having done the same, on a different app. With the hosts not responding to messages…

Oct 8, 2025

Desire, Duty, and Deception Collide

Carmen Emmi’s Plainclothes is an evocative, bruising romantic thriller that takes place in the shadowy underbelly of 1990s New York, where personal identity collides with institutional control. More than just a story about police work, the film is a taut…

Oct 8, 2025

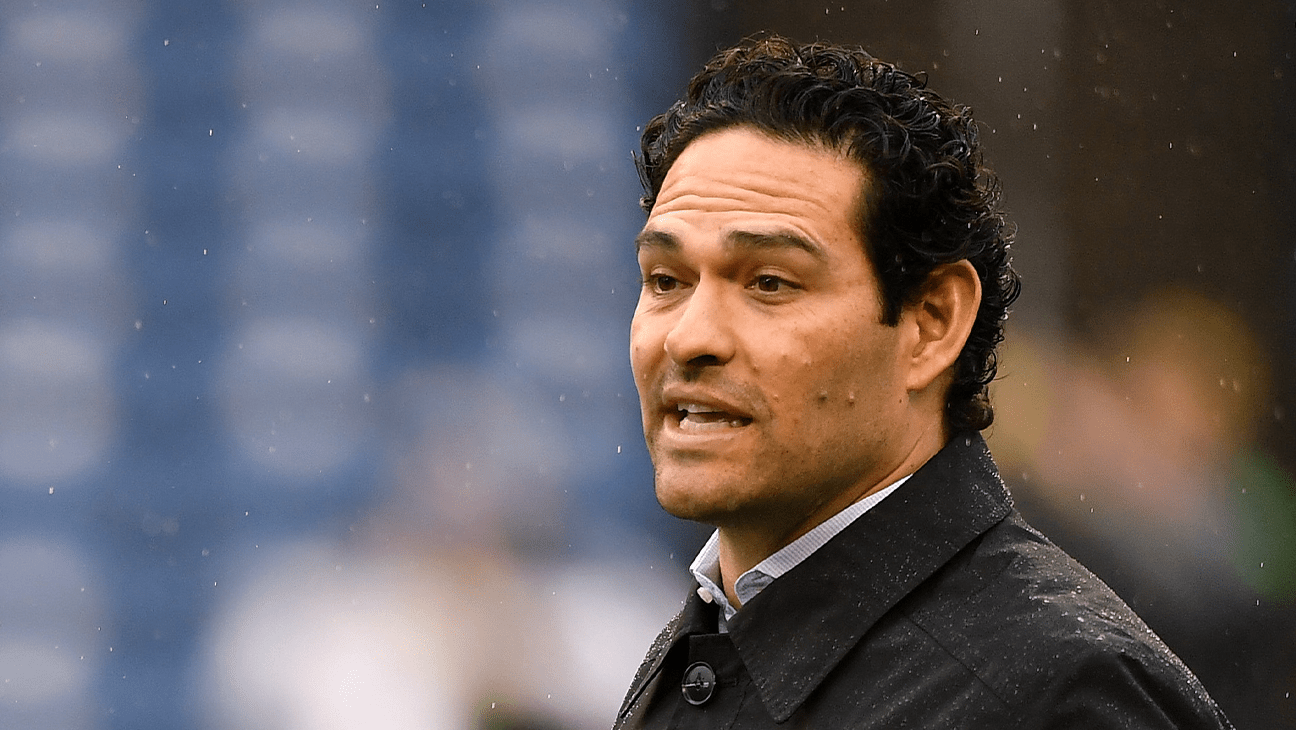

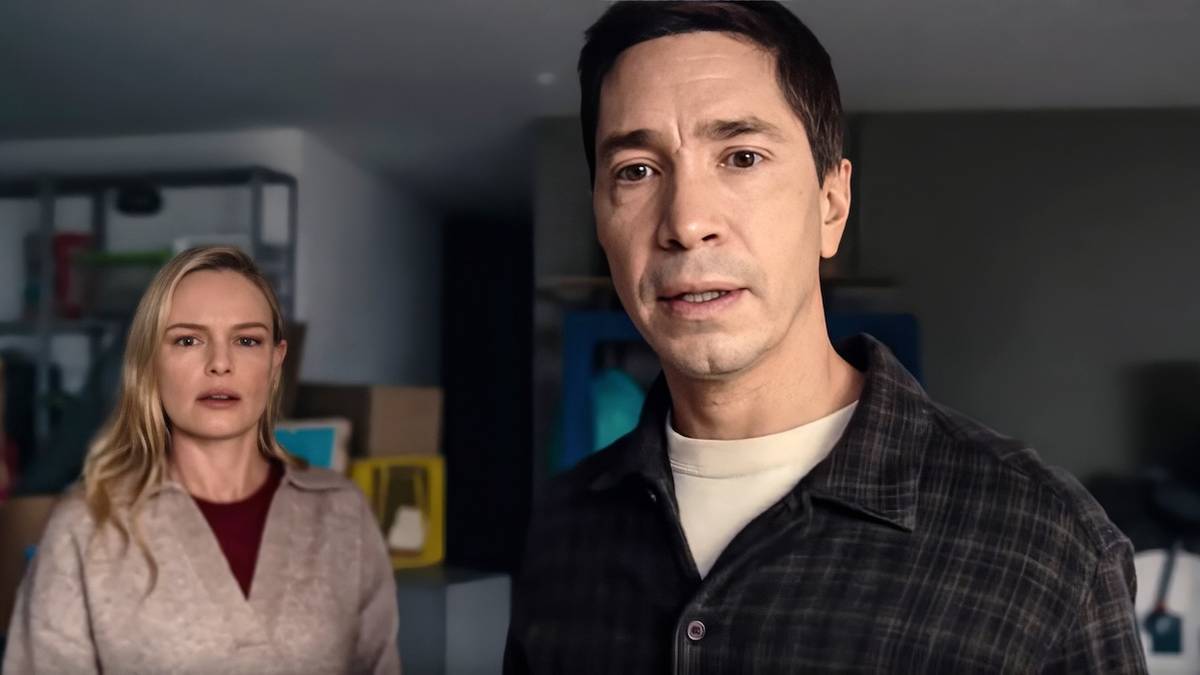

Real-Life Couple Justin Long and Kate Bosworth Have Tons of Fun in a Creature Feature That Plays It Too Safe

In 2022, Justin Long and Kate Bosworth teamed up for the horror comedy House of Darkness. A year later, the actors got married and are now parents, so it's fun to see them working together again for another outing in…

Oct 6, 2025

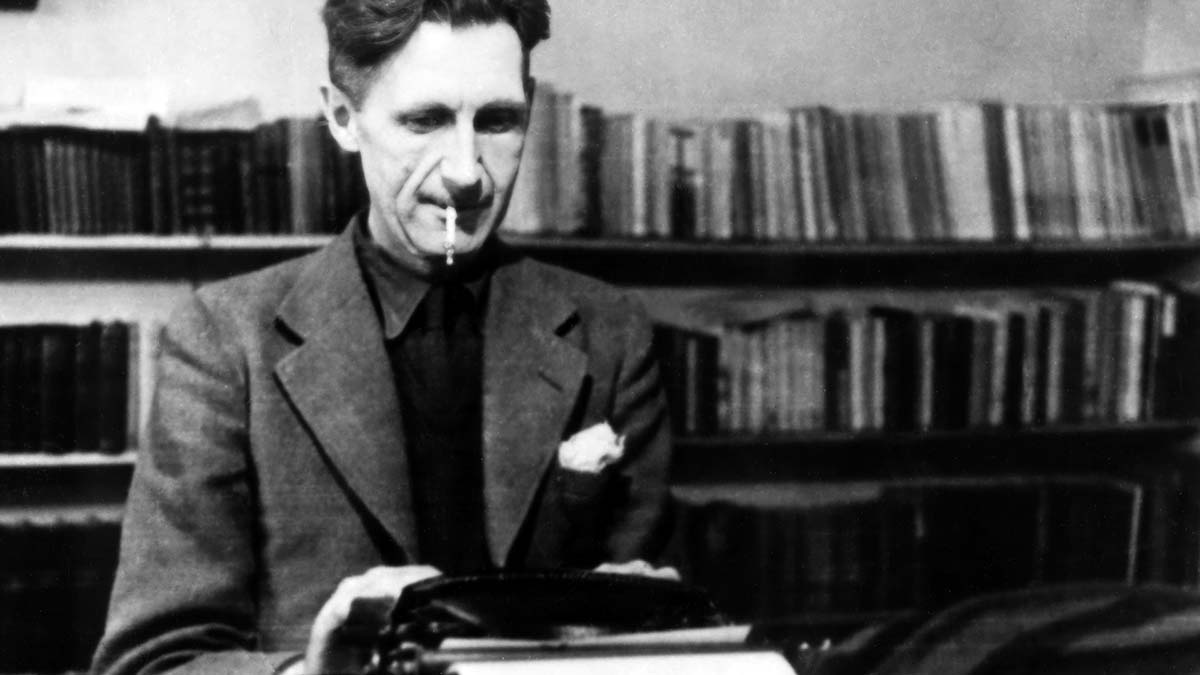

Raoul Peck’s Everything Bagel Documentary Puts Too Much In the Author’s Mouth [TIFF]

Everyone has their own George Orwell and tends to think everyone else gets him wrong. As such, making a sprawling quasi-biographical documentary like “Orwell: 2+2=5” is a brave effort bound to exasperate people across the political spectrum. Even so, Raoul…

Oct 6, 2025