NYFF Title Howard Brooknerâs âRobert Wilson and the Civil WarsâFilmmaker Magazine

Sep 30, 2025

Robert Wilson and the Civil Wars

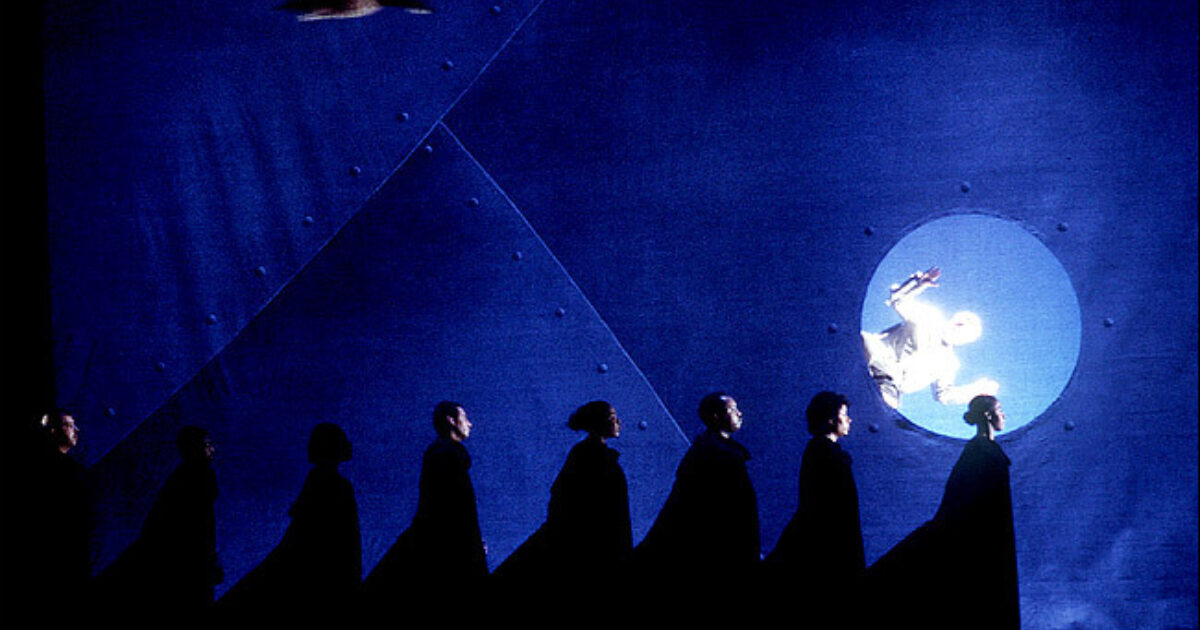

While many (likely most) maverick artists have at least one unrealized moonshot project, few have a record of the high stakes drama of development behind the scenes of that lost dream. And even fewer have a record that’s as cinematically riveting as Howard Brookner’s Robert Wilson and the Civil Wars, a fascinating look at the titular theater legend as he goes about crafting — artistically, managerially, financially — the CIVIL warS: a tree is best measured when it is down, his massive, multinational, 12-hour opera for the 1984 Summer Olympics. And far fewer documentarians have a nephew like Aaron Brookner, who’s spent the past dozen years painstakingly restoring his uncle Howard’s long-unseen film.

Premiering at this year’s New York Film Festival, the newly restored version (from a surviving 16mm print) is a deft interweaving of clips of Wilson’s outsized stage works with up-close interviews with both collaborators and the surprisingly transparent theater titan himself, sometimes in laidback settings, such as squeezed between former neighbors on a couch in his childhood hometown of Waco, Texas. Indeed, it’s Howard’s truly intimate access -—an overused term when it comes to docs -—to his lead character that humanizes this abstract avant-garde world. You really get the sense that Wilson’s just hanging out unfiltered with a friend who happens to have a camera, which was probably the case.

There’s Philip Glass, who in response to Howard’s questions about Einstein on the Beach, says that it’s hard to describe something with words that wasn’t based on language to begin with. And Wilson’s partner on the German script, Heiner Müller (disciple of Brecht and member of The Berliner Ensemble), who aims to create a “theater of experience,” not a “theater of discourse” – one in which “you might only understand what you saw weeks later.” At one point Wilson even confesses that the older he gets the more he realizes that he has to make compromises, an unexpected admission coming from a detail-obsessed man for whom paring down seems an utterly foreign concept.

Just prior to the Lincoln Center debut (September 29th) of Robert Wilson and the Civil Wars, Filmmaker reached out to Aaron Brookner, who we last caught up with to discuss his Locarno-debuting Nova ’78). In addition to pursuing a home for his uncle’s archives, Brookner is now also busy developing his own films and series as co-director of Pinball London.

Filmmaker: You began work on your uncle’s archive with 1983’s Burroughs: The Movie back in 2012, and just this summer premiered Nova ’78, which resurrects your uncle’s late-’70s footage from the three-day Nova Convention, at Locarno. Now you’re debuting Robert Wilson and the Civil Wars, which played festivals and on public TV in the mid-’80s. So how different — or similar — were all these restoration processes?

Brookner: They were all different, really. For Burroughs we had hoped to find the negative of the film, but what we found were all the negative rolls of footage that never made the final cut (the biggest part of Howard’s archive). So we were working from a print for Burroughs. The print and the sound both needed careful work, but the print had been well-preserved and was in good condition, with a synced sound track.

With CIVIL warS there was no sync audio, and no separate audio soundtrack start-to-end that at some point did not have dubbing. There was also no negative, and the best available print had damage (scratches, etc.). So what happens is you need to walk a fine line between how much you can clean and repair without negatively affecting the image, and the inherent grain structure of the film. I should add that both the films were 16mm, so there is grain and that’s important to the look. If you go too far it starts to look weird. Also, film is alive in a way. It can decay and degrade. And the CIVIL warS print had degraded and changed color. So this was another challenge.

Lastly, with Nova we were working from negative rolls that had been stored differently from the previous Nova Convention negative rolls we’d uncovered in 2014. It’s a good case study in film preservation: one set of negatives shot at the same time and place, stored in different settings over many years…looked very different. And some of the rolls had a lot of damage too. We had to repair the damage, find the sound for these negative rolls, manually sync them to picture, and then find a common color grading so that the two sets of Nova reels could unite as one for a coherent film.

I would also add that over these 13 years technology has rapidly changed. New tools became possible that weren’t before.

Filmmaker: It’s taken you around a dozen years to realize this project, so I’m curious to hear about some of the biggest challenges. Was financing a major obstacle?

Brookner: Financing was a major obstacle of course, especially considering the economics of bringing back an older film. It’s an expensive process in the best of situations, and we all know how hard our industry is on distribution for independents. But given that we knew the print we had would need a lot of work, plus the sound, coupled with the fact that very few people know about this film, made not just the raising of money hard but the planning too. Plus it took time to scour for all the elements because in any restoration you have to work with the best options available, and this requires due diligence. It’s also very hard to bring back a film when the director and producer (Howard) is not there to ask any questions of. And his US co-producer Orin Wechsberg lost all his materials to Hurricane Sandy, then sadly passed away six years ago. Toss a global pandemic in the middle of it all, you got a lot of challenges.

When I set out to make Uncle Howard I faced this challenge of how do you tell a story about a filmmaker whose films are forgotten and not that many people know. You gotta show it — so I made that movie. Similarly with CIVIL warS, few people knew the film, which was a big and parallel challenge. I knew the film and how great it is. But in practical terms that meant sort of having to show it to prove it.

Filmmaker: Could you talk a bit about piecing together the audio? I believe you relied on video tapes and magnetic tapes.

Brookner: Piecing together the audio was a Frankenstein job because there was not a single version (optical sound, VHS, mag roll) that didn’t have some dubbing over voices. It really sets a different tone when that happens. I have to really commend my partner on this, (Pinball founder) Paula Vaccaro, who fought to keep on the hunt for audio even when it felt like we’d exhausted all possibilities.

At one stage we worked with a studio on the sound, but the results didn’t hold and we ended up starting over from scratch. That’s when Dan Zlotnik came in, recommended through our post supervisor Carlos Morales. With him we could finally pull together all the fragmented sources into one coherent mix.

Over time we managed to construct a soundtrack that was original language except for one part in French. I had paid a lab ,and we were going through the very last possibilities. I thought we were done. I had one more VHS tape, which was an Italian version, so I assumed it was fully dubbed. Remarkably, there was no dubbing at all; and no narration either, but that was fine because all I needed was the French part. Not only was it clean, but in the middle of the interview Howard asks a question I’d never heard. That it was the final piece was really quite chilling. It was actually a very powerful moment.

I’d also like to give a big shout out to the many talented people who helped us work these fragmented parts of the sound, different frame rates, pitches and formats, into one new mix.

Filmmaker: Did you elicit feedback from Robert Wilson — or any of the participants and crew — as you worked on the film? Who’s seen the restoration – and what’s been the response?

Brookner: Bob and I spoke at length about CIVIL warS throughout the process — the progress, the pitfalls, etc. He was always very encouraging and positive. As far as the crew, I spoke to Tom DiCillo of course, who shot part of it, but most of the crew I didn’t know. And sadly, Howard and Orin were not around.

For many years Howard’s German co-producer was MIA, but now he’s coming to see the film in New York! I’m very excited for that. In addition, Bob Chappell, who was also a cinematographer, will see it. I’d only managed to get in touch with him thanks to digging and finding Orin’s widow, and his ex-wife, who was quite involved with them when they were making this.

So there will be a reunion of sorts around this film, which is very beautiful. A testament to what films mean and can do for our community. So far the audience in Bologna at Il Cinema Ritrovato have seen the film and were really thrilled and stirred by it. It is such a finely crafted film, where you not only get inside Bob’s personal story and his work, but feel the emotion of what it’s like to create under intense pressure and high stakes. Also, it’s not every day you get to see a “revival” or a “classic” of a film you never knew existed. It’s pretty cool.

And of course, thankfully, Bob was also able to see the film in Bologna, just a few weeks before he passed. He had made a big effort to get there, and I’m so glad he did. It meant a lot to him and to me as well to watch it with him on a big screen in a theater. I’m very grateful for that experience.

Filmmaker: I’m also curious to hear about the lessons you’ve learned over the years of working with this vast archive, including the mistakes you may have made throughout this time. Anything you would have done differently?

Brookner: Gosh, I don’t know if there’s any mistakes because it’s not like there is a particular roadmap to follow, nor are there infinite resources. It’s really hard to organize something that was done by someone else, and who isn’t around to ask what is what. Organization is key. Staying up with preservation and archiving is key, and needs regular tending. Also, technology changes. Which is a blessing, because there are many new tools now that are really phenomenal that didn’t exist years back; but at the same time it works the other way, so technical work done years ago may need to be revisited in time to bring it up to speed.

Sound was a particular learning curve. We went through trial and error, and in the end discovered a whole toolbox of techniques for restoring both image and audio. That experience was tough but invaluable. Today we’re even advising other filmmakers on how to deal with their own archives. We hope to pass on the knowledge we’ve gathered to help other collections that may need it.

Publisher: Source link

Erotic Horror Is Long On Innuendo, Short On Climax As It Fails To Deliver On A Promising Premise

Picture this: you splurge on a stunning estate on AirBnB for a romantic weekend with your long-time partner, only for another couple to show up having done the same, on a different app. With the hosts not responding to messages…

Oct 8, 2025

Desire, Duty, and Deception Collide

Carmen Emmi’s Plainclothes is an evocative, bruising romantic thriller that takes place in the shadowy underbelly of 1990s New York, where personal identity collides with institutional control. More than just a story about police work, the film is a taut…

Oct 8, 2025

Real-Life Couple Justin Long and Kate Bosworth Have Tons of Fun in a Creature Feature That Plays It Too Safe

In 2022, Justin Long and Kate Bosworth teamed up for the horror comedy House of Darkness. A year later, the actors got married and are now parents, so it's fun to see them working together again for another outing in…

Oct 6, 2025

Raoul Peck’s Everything Bagel Documentary Puts Too Much In the Author’s Mouth [TIFF]

Everyone has their own George Orwell and tends to think everyone else gets him wrong. As such, making a sprawling quasi-biographical documentary like “Orwell: 2+2=5” is a brave effort bound to exasperate people across the political spectrum. Even so, Raoul…

Oct 6, 2025